Willi Hennig (Image by Gerd Hennig, CC-license, Wikipedia)

The science of taxonomy is rooted in history, with every taxonomist standing on the shoulders of giants that came before. Some of these giants are well known outside of taxonomic circles: Carl Linnaeus, the godfather of taxonomy who categorized life and introduced binomial nomenclature; Charles Darwin & Alfred Russel Wallace, co-discovers of evolution through natural selection and both prolific descriptive taxonomists in their own right. A lesser known giant, Willi Hennig, was not only a brilliant taxonomist, but also revolutionized the way in which we study & reconstruct species relationships. Today (April 20, 2012) marks what would have been his 99th birthday, and in his honour, I invite you to sit back and allow me to tell you a story of flies, war and why you & I are fish.

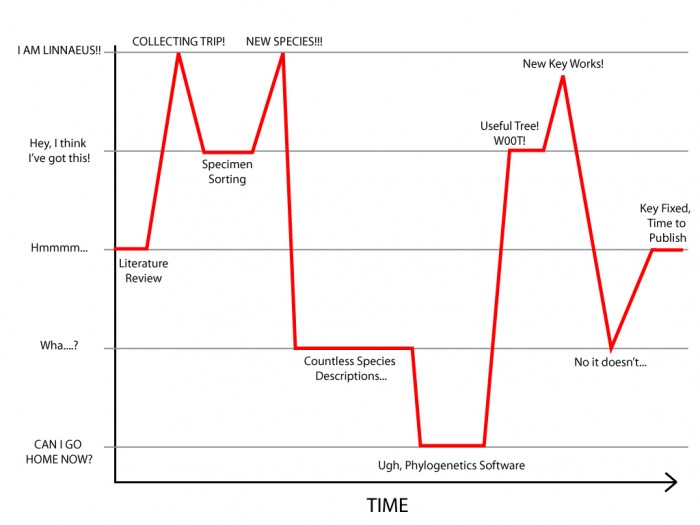

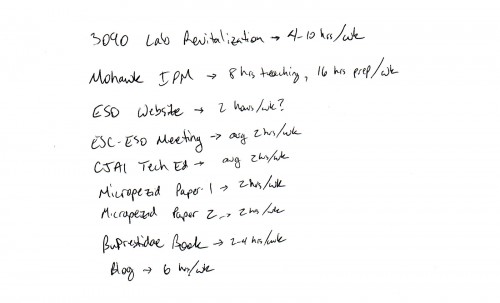

Willi Hennig was born April 20, 1913, the eldest son of working class parents, in Dürrhennersdorf, Germany. Hennig excelled throughout his schooling, developing a passion for insects by the 5th grade, and began working at the Dresden State Museum of Natural History while still a teenager. After a few years studying the taxonomy of reptiles, Hennig found his true passion, dipterology. Starting somewhere between 1932 and 1934, Hennig began revising the stilt-legged flies (family Micropezidae), completing his revision in 1936. Hennig erected 10 new genera and described 93 new species over several papers spanning 300+ pages. Concurrently, Hennig found time to publish papers on stilt-legged fly biogeography, more reptile taxonomy, and he also completed his PhD (on the copulation apparatus and system of the Tanypezidae; another lineage of acalyptrate flies), all before he was 24.

This stilt-legged fly belongs in the genus Poecilotylus, one of the genera Hennig created in his early Micropezidae work.

Hennig was beginning to rethink how species were related, but before he could further explore his ideas, German politics and a world at war intervened.

Enlisted into the German army in 1938, Hennig fought for Nazi Germany (though he was never a member of the National Socialist party) until 1942 when he was severely injured while fighting in Russia. After recovering from his injuries, Hennig was posted to Italy as a military entomologist and put to work on malaria prevention. In May of 1945, as the war was nearing an end, Hennig’s unit was captured by British soldiers, and he became a prisoner of war. His British captors recognized Hennig’s potential, and rather than placing him under confinement in a prison camp, allowed him to continue his work on malaria for the benefit of the Queen.

For 5 months while confined to the “service” of the British army, Hennig refined his hypotheses on the evolutionary history of species. With the help of his wife Irma, who corresponded with colleagues and journals on his behalf (because he continued to publish throughout the war), and who included hand-written excerpts of the scientific literature in her letters to him, Hennig completed his first draft of one of the most important biological manuscripts of the 20th century, all by hand while a POW, prior to his release in October, 1945. It would be another 5 years until his book would be published in Germany because of a paper shortage, and a further 16 years until the English-speaking world was introduced to Willi Hennig’s revolutionary Phylogenetic Systematics.

Prior to Hennig’s book, species (and higher taxa) were clustered by overall similarity without regard for their evolutionary history, a method known as phenetics. What set Hennig’s phylogenetic systematics apart was the idea that species evolved from one another, and thus species should be classified as complete units descended from a recent common ancestor (a concept known as monophyly).

Phenetics vs Monophyly (Modified image from lattice CC-BY)

Think of a tree; with phenetics, leaves from different branches could be grouped together because they looked the most similar to one another. Phylogenetic systematics on the other hand, posited that only leaves arising from a shared branch should be classified together, regardless of how those leaves may look. How do you know the origin of the branch when all you have in front of you are the leaves? Hennig’s answer was to find defining characters or traits that were unique to the tip branches but which were different from the branches closer to the trunk of the tree.

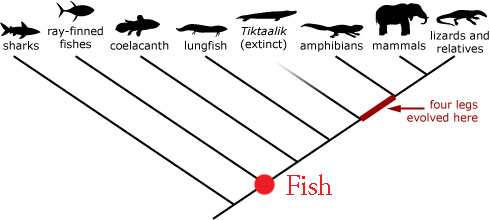

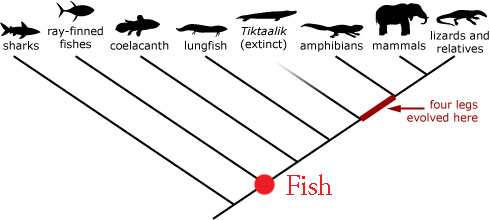

It’s Hennig’s concept of monophyly that makes us all fish. You see, what we call fish, tasty aquatic vertebrates with fins and gills, are actually a number of different evolutionary lineages, each arising successively like twigs off a tree branch. One of those twigs near the end of the branch became the terrestrial vertebrates, which in turn has smaller twigs each representing amphibians, reptiles, birds (which are actually reptiles for the same reason we’re fish) and mammals. So, if we consider separate twigs of aquatic, gilled vertebrates as “fish”, then we must also consider our twig of terrestrial vertebrates “fish” since the most recent, common ancestor of all the “fish” also gave rise to us!

Fish Phylogeny (Image modified from Understanding Evolution)

In retrospect it seems a simple idea that species should follow a branching pattern from a common ancestor like Hennig proposed, but the upheaval of decades of work on species relationships was indeed revolutionary, and was viciously opposed by many biologists. In fact it wasn’t until the late 1980s that phylogenetic systematics came into vogue, in most part thanks to a new, young cohort of taxonomists who adopted the moniker of “raving cladists”.

Hennig meanwhile, continuing his work with flies, applied his phylogenetic systematics across a large diversity of dipteran families, examined flies sealed in ancient amber for evidence of ancestral characters, and published dozens of papers (across thousands of pages) that redefined the higher relationships among flies and described new species. It was at work in his museum that Hennig preferred, only twice venturing from Germany to examine fly collections in Australia, the USA, and Canada, where he spent several months working in what is now the Diptera Unit of the Canadian National Collection of Insects in Ottawa.

Oh, to be a fly on the wall in this room for a day! So much dipterological knowledge all concentrated in one room, it must have been amazing. Back row from left: Frank McAlpine, Herb Teskey, Guy Shewell. Front row from left: Monty Wood, Dick Vockeroth, Bobbie Peterson, Willi Hennig. (Image from Cumming et al, 2011)

Willi Hennig wouldn’t survive to see his work become fully appreciated by the scientific community. After a normal day working in his museum looking at larval flies, Willi Hennig suffered a heart attack and died at home on November 5, 1976. Although he died much too young, his legacy lives on; his work with stilt-legged flies is second to none, many of his hypotheses regarding the higher relationships of flies are being supported with new DNA data, and biologists around the world use phylogenetic systematics on a daily basis.

Happy Birthday Willi, and thanks for all the fish.

Willi Hennig (Image by Gerd Hennig, CC, Wikipedia)

———————————-

All biographical information was taken from the following sources:

Byers, George W. 1977. In Memoriam: Willi Hennig (1913-1976). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society, 50 (2): 272-274. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25082934?origin=JSTOR-pdf

Kluge, Arnold G., Bernd Hennig. No Date. Willi Hennig. Willi Hennig Society – http://cladistics.org/about/hennig

Schmitt, M. 2003. Willi Hennig and the Rise of Cladistics. Proceedings of the 18th International Congress of Zoology: 369-379.

Dipterist Group Photo:

Cumming, Jeffrey M., Bradley J. Sinclair, Scott E. Brooks, James E. O’Hara, Jeffrey H. Skevington. 2011. The history of dipterology at the Canadian National Collection of Insects, with special reference to the Manual of Nearctic Diptera. Canadian Entomologist 143: 539-577.

sciseekclaimtoken-4f850e14c19e1