When taxonomists discuss gender, they’re usually debating whether the etymological root of a species name is the same gender as the root of its genus, and whether that species name should end with –i, –a, or perhaps –us. While debating ancient Latin grammar may be a noble, if occasionally dull, pursuit, there’s a more important discussion on gender in taxonomy that we need to be having; why women continue to be underrepresented in our discipline.

I’ve been somewhat aware of the gender disparity in taxonomy for a while—I’ve casually noticed how few women are currently employed in natural history collections or as professors of taxonomy & systematics at universities, and that there are relatively few women attending taxonomic meetings, particularly outside of students and post-doc positions—but the issue burst into my consciousness like a slap to the face recently as the journal ZooKeys celebrated their 500th issue.

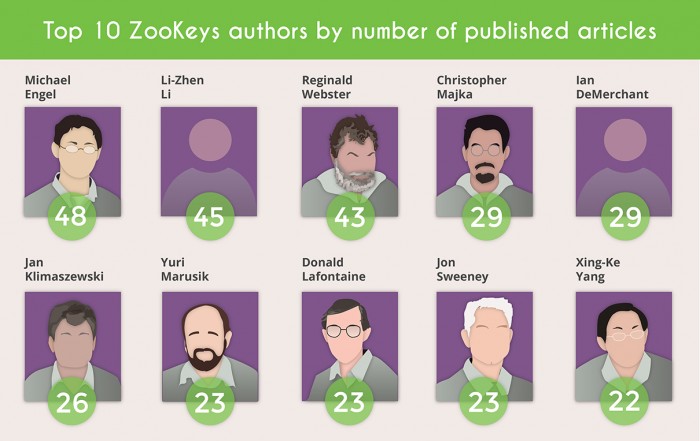

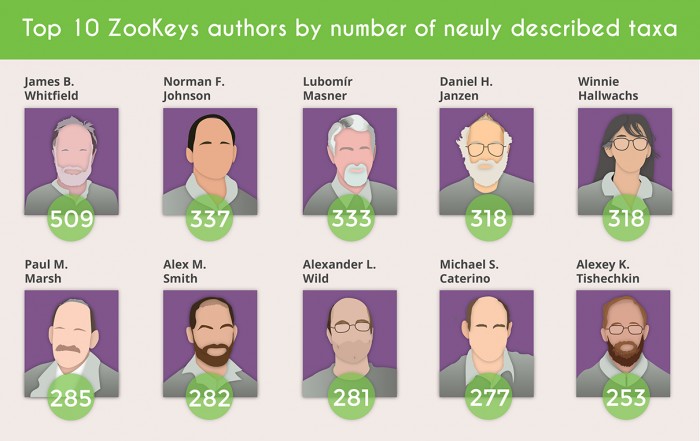

As a part of the celebration, ZooKeys created a series of Top 10 posters that they shared on social media, recognizing the editors, reviewers, and authors who have helped the journal become one of the most important venues for zoological taxonomy over the last 7 years. Check them out:

Of the 35 people being recognized for their contributions to publishing & the taxonomic process, in categories that are highly regarded and influential in hiring & promotion decisions, only 1 is a woman. I doubt ZooKeys could have created a starker depiction of gender disparity in taxonomy had they tried.

What’s going on here? How can only 1 woman be included in these lists? Hoping that it was some random fluke, I started looking around for more information on gender diversity in the taxonomic community, and well, it didn’t get better.

First, I looked at the editorial board & section editors for ZooKeys, and found only 1 woman sat on the editorial board, out of 15 members (6.7%), while only 37 of the 265 section editors were women (14%). When I compared this to Zootaxa, the other major publisher of zoological taxonomy, I found the exact same ratio among section editors, 14% (32/225). Systematic Biology? A slightly better 15 for 80 (19%), while Systematic Entomology is 3 for 18 (17%) and Cladistics is only 2 for 20 (10%). Even the small biodiversity journal for which I’m the technical editor only has 2 female editors out of 15 (13%). Meanwhile, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, the governing body that sets the rules for naming animals and adjudicates disputes over names, currently has 23 male commissioners, and only 4 women (15%).

Compare this to ecology, where Timothée Poisot reports 24% of editors for the more than a dozen journals he’s looked at are women, while Cho et al. (2014) found editorial boards in other biological fields to be roughly 22% women in 2013 (up from ~8% in 1990). Clearly 22-24% is a far cry from parity, but it’s still 10% higher than it is in taxonomy.

But is this indicative of the true diversity of taxonomists? It’s hard to say. In 2010, the Canadian Expert Panel on Biodiversity Science surveyed taxonomists in Canada, and reported that 139 of their 432 survey respondents identified as women (30%). Ironically, the panel itself only included 3 women (out of 14; 21%), and only 2 women reviewers (out of 12; 17%), failing to accurately reflect the community it was attempting to assess. Meanwhile, the UK’s House of Lords Science and Technology committee on Taxonomy & Systematics (2008) reported only 143 of 861 UK taxonomists were women (17%), but while there was much discussion over the potential decline in total numbers of taxonomists, there was none regarding gender inequality.

Looking more broadly, 42% of science & engineering PhDs were awarded to women in 2013, and 28% of applicants to the NSF Division of Environmental Biology (the major funding source for ecology, evolutionary biology and taxonomy/systematics in the USA) in 2014 were women, so it’s not unreasonable to assume the professional taxonomic community is at least 25% women, and hopefully much higher. Again, 25% is a long ways from equality, but it still suggests there is a definite misrepresentation of diversity on the editorial committees of taxonomic journals.

So why does it matter if editorial boards and reviewer pools aren’t representative of the community, whether it be in terms of gender or ethnicity (another important discussion the taxonomic community should be having)? Well, for one, keeping taxonomic publishing an Old Boys Club is more likely to result in situations like that which recently occurred at PLoS ONE, with biased, sexist, and misogynistic attitudes influencing not only the publication of research, but by extension, the career advancement (or lack thereof) for taxonomists based solely on their gender. Now, I’m not saying that the editors and reviewers for ZooKeys & Zootaxa are explicitly engaging in biased behaviour, but recent research has shown the implicit biases of academia towards women, particularly in publishing, and there’s no reason to assume taxonomy is immune to these factors.

But there’s also the fact that female early career taxonomists may look at the editorial boards of these journals, or see posters of those being recognized and praised for their contributions, and not see anyone that looks like them in a position of power. Having role models with whom one can identify with is an important influencer, and after 250 years of old white dudes at the helm, it’s unfortunately not difficult to see why gender diversity in taxonomy is where it is.

So where do we go from here? How can we encourage more women to pursue a career in taxonomy and bring their passion for the natural world along with them? Well, for starters, we should be inviting more women to become editors for our journals, but we also need to start talking about gender equality in taxonomy, and our failings therein, more openly. The statistics on women in taxonomy from the Canadian Expert Panel on Biodiversity Science weren’t mentioned at all in the main body of the report, but were instead relegated to the appendices. Worse, the 2010 UK Taxonomy & Systematics Review didn’t include data on gender diversity in taxonomy, instead focusing on funding and age demographics; perhaps illustratively they titled the demographics section “Current Manpower and Trends”.

Ignorance of gender disparity in taxonomy is no longer acceptable; there is no excuse for convening a panel discussion on “The Future of Diptera Taxonomy & Systematics” at an international meeting and only inviting male panelists. As a community, we need to change the way that we go about our work so anyone with an interest in biodiversity feels welcome and able to contribute to our collective knowledge of Earth’s species. Just as we are compelled to debate the etymology of a dead language, we must be equally compelled to create a vibrant taxonomic future based on equality and diversity.

UPDATE (12:02p 05/07/15): Ross Mounce pointed me to a paper that was just published this week that examines the role of women in botanical taxonomy, and they present data that is equally bad to my numbers above. Of the nearly 625,000 plant species described over the last 260 years, a paltry 2.8% were described by women. Additionally, only 12% of authors in botanical taxonomic papers were women. Read the paper in its entirety in the journal Taxon.

——-

Cho A.H., Carrie E. Schuman, Jennifer M. Adler, Oscar Gonzalez, Sarah J. Graves, Jana R. Huebner, D. Blaine Marchant, Sami W. Rifai, Irina Skinner & Emilio M. Bruna & (2014). Women are underrepresented on the editorial boards of journals in environmental biology and natural resource management, PeerJ, 2 e542. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.542

——-

For the biodiversity data scientists reading this, a challenge: what proportion of authors in taxonomic papers are women, are they more likely to be first author, last author, or somewhere in the middle, and what proportion of taxa have been described by women? I think these statistics should be relatively easy to figure out, especially with services like BioStor & BioNames, and will help us better understand gender diversity in taxonomy, both historically and as we move towards the future. And perhaps consider publishing your results in the Biodiversity Data Journal, which has editorial gender issues of its own (editorial board: 1/14 (7%); section editors: 28/161 (17%)).