Some how it’s already December 31st, which besides being terrifying that another year has come and gone, also makes it time for a look back at the year that was — because honestly I feel like I blinked and missed it all!

2012 was a crazy year for me. Between finishing up the field guide, developing & teaching my first college-level course, starting my PhD and travelling to several meetings and workshops across North America, I saw and did a lot of new stuff that I’m grateful to have been able to do, and feel like the year was a pretty productive one overall (although I failed to get a few papers out that I had hoped to and which continue to hang over my head…).

In addition to the “traditional” measures of academia, 2012 was a big year for alternative projects as well. I joined up with Crystal “The Bug Geek” Ernst to start the ESC Blog, started co-hosting a podcast with some really awesome people, participated in a journal club made possible because of social media, and interacted with a ton of amazing people online, who all inspired me, stimulated my mind and provided a much needed stress release!

Here at the blog I found myself battling periods of writing cramps and unwanted mental vacations, but still managed to come up with 79 posts (including this one). As for readers and visitors, 2012 was a banner year for my blog, with more then 25,000 people from 160 countries & territories stopping by to read articles or look at photos. In case you’re interested, my most read posts this year were:

- Field Guide to the Jewel Beetles of Northeastern North America – 5.5k views

- New species wants you to See No Weevil – 5k views (largely because it was featured by both Jerry Coyne at Why Evolution is True & Ed Yong at Not Exactly Rocket Science — OMG)

- Like a Deer Fly in the Headlights – 3k views

For comparison, the 3 posts which I enjoyed writing the most were:

- Dipterist Files – Willi Hennig

- Twitter for Scientists (and why you should try it)

- Irreplaceable fly described from Australia

I tried out some new ideas this year, stirred a few pots, and feel like I’ve made some pretty decent advances with my writing overall. No complaints there!

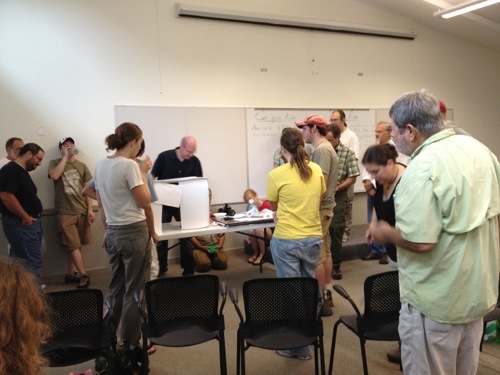

The one area that I feel like I failed at in 2012 is taking the time to pick up my camera! I only kept 1350 photos this year, and a large proportion of those don’t meet my standards for sharing here, or are of family. The number of bug photos I took would have been much lower had I not been at BugShot, which gave me a big kick in the pants to get out there and enjoy some free time. While I didn’t take as many photos as I would have liked, I did come away with some that I’m quite happy with. Some of these I’ve previously blogged, but most of these have been locked away in my hard drive until now, so enjoy!

Favourite Photo of the Year

Favourite Fly Photo of the Year

Favourite Photo of a Newborn Fly

Favourite Photo of a Fly Annoyed by my Presence

Favourite Bug Porn Photo

Favourite White Box Photo

Favourite Photo Using Techniques Learned from another Bug Blogger

I ended up with SO MUCH SAND DOWN MY PANTS after using Ted MacRae’s patented Tiger Beetle Stalking Crawl… Cicindela scutellaris – Norfolk County, Ontario

Favourite Photo of a Bug Blogger Caught Posting to Twitter

Favourite Photo of a Parasite Freshly Excavated from a Lab Mate’s Foot

Chigoe Flea (Tunga penetrans) female – Guelph, Ontario (originally “collected” in Guyana). Look for a full write up and photo essay about this creepy insect soon (I promise).

Favourite Landscape Photo

Favourite Photo of an Insect Sitting on Santa’s Lap

All I want for Christmas are my 2 front wings! Manduca sp. (labelled Tomato Hornworm at the pet shop) posing with Santa – Guelph, Ontario

Favourite Photo that Keeps Me Taking Photos Because I Just. Barely. MISSED IT!!

The one that got away — from me at least, I’m pretty sure that wasp is doomed. If only I had focused a few millimeters closer to me… Sigh

And finally…

Favourite Photo of My Wife, Who Makes it All Worthwhile