![]() It’s not often that flies make headlines, and when they do it’s usually in a negative connotation (malaria, mosquitoes, black flies, etc). A new paper published Tuesday in PLoS ONE (Core et al, 2011) is certainly not helping this Detrimental Diptera Dillema (DDD), announcing that a species of scuttle fly (Phoridae) has been discovered parasitizing honey bees (Apis mellifera), one of the most loved insects on the planet.

It’s not often that flies make headlines, and when they do it’s usually in a negative connotation (malaria, mosquitoes, black flies, etc). A new paper published Tuesday in PLoS ONE (Core et al, 2011) is certainly not helping this Detrimental Diptera Dillema (DDD), announcing that a species of scuttle fly (Phoridae) has been discovered parasitizing honey bees (Apis mellifera), one of the most loved insects on the planet.

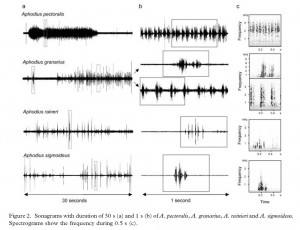

Of course things attacking honey bees isn’t in itself news, especially in the age of Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). The real news here is that the scuttle fly, Apocephalus borealis, has seemingly switched hosts, previously known to be parasitic in bumble bees, paper wasps, and even black widow spiders (Brown, 1993). Other Apocephalus flies are better known as ant-decapitating flies, who’s larvae will pupate in the dismembered heads of their ant hosts. As for A. borealis, it’s association with honey bees was thanks to a serendipitous natural history observation:

(John) Hafernik, who also serves as president of the California Academy of Sciences, didn’t set out to study the parasitized bees. In 2008, he was just looking for some insects to feed the praying mantis that he had brought back to SF State’s Hensill Hall after an entomology field trip. He scrounged the bees from underneath the light fixtures outside the biology building.

“But being an absent-minded professor,” Hafernik joked, “I left them in a vial on my desk and forgot about them. Then the next time I looked at the vial, there were all these fly pupae surrounding the bees.”

– San Francisco State University Press Release, January 3, 2012

After further observation, a few behavioural trials and some interesting molecular techniques, the research team found that not only were these scuttle flies parasitizing honey bees in the San Francisco Bay area, but also in migratory bee colonies housed in the Central California Valley and South Dakota, and also that infected honey bees would leave their colonies at night to fly away and die (often congregating at man-made lights and acting strangely); that all of the parasitized bees had been exposed to Nosema ceranae (a fungus which can lead to death from diarrhea and malnourishment) and/or Deformed Wing Virus (a disease that can cause malformation of a bee’s thorax and wings during pupation); and that some of the flies had evidence of these bee pathogens in their systems.

This is a lot of really interesting information for one study, but it’s not hard to see where the authors were going next with their story: scuttle flies could be contributing to CCD and posed a “new threat” to honey bees. The authors proceeded to pose a long series of questions regarding future areas of research, and how all of their findings could be detrimental to honey bee populations and the potential role these flies play in CCD. Overall, this is a very cool piece of natural history research, with a bit too much CCD hype for my liking!

—

You can see why the media has fallen in love with this paper; it includes flies (which no one likes on principle), honey bees (which everyone likes on principle), CCD (which scares the daylights out of everyone) and zombies (which also scare the daylights out of everyone). At the time that I wrote this post (midnight-ish Wednesday morning), I found 13 major news outlets or blogs from around the world which had covered the story (see list below).

This is where we have a problem though. Of the 13 stories I looked at, 8 of them had errors in their reports, of varying severity. What’s worse, all of the erroneous accounts were in major reporting outlets, potentially misinforming thousands of readers! It’s not surprising however, to see that 7 of the 8 stories that got things 100% correct were all science-focused publications/blogs, while one was a small-market news affiliate:

The Good

KQED News – ‘Zombie’ Parasite Preys on Bay-Area Honeybees, by Lauren Sommer

Observations (Scientific American Blog Network) – “Zombie” Fly Parasite Killing Honeybees, by Katherine Harmon

New Scientist Life – Parasitic fly could account for disappearing honeybees, by Andy Coghlan

Science Now – Parasitic Fly Dooms Bees to Death by Maggots, by Erik Stokstad

Myrmecos – Did a parasitic fly cause Colony Collapse in bees?, by Alex Wild

Not Exactly Rocket Science – Parasitic fly spotted in honeybees, causes workers to abandon colonies, by Ed Yong

The Bad

MSNBC (WebCite copy) – Stated bees which foraged at night were more likely to be parasitized than bees that foraged during the day (misinterpretation of Fig. 3A of Core et al., 2012)

Mirror (WebCite copy) – Stated that the parasite “is similar to one being found in bumblebees” (it’s not just similar, it’s the same species)

Press Association (WebCite copy) – Title states that the flies are linked to bee losses (not true, the connection between fly parasitism and CCD is simply proposed by the authors); Implied that bees are immediately turned into light-seeking zombies after the female fly lays her eggs (it appears to take up to a week for this to happen)

Daily Mail Online (WebCite copy) – Title states link between flies and global decline of bees (see above); Didn’t italicize species names (minor I know, but it bugs me)

CBC News (WebCite copy) – Implies that bees which foraged at night were more likely to be parasitized than bees that foraged during the day (see MSNBC)

io9 (WebCite copy) – “This parasite is a likely culprit (in reference to CCD – MDJ) because it does indeed force bees to abandon their colony” (authors say the fly may contribute to CCD, not that it is the likely culprit)

Daily Express (caching not allowed) – Implies that bees are parasitized in their hives and that they immediately “abandon their hives in a crazed state” (the authors are unsure of where the flies attack, but they know it’s not in the hive, and see the Press Association above); didn’t italicize species names (argh)

While I doubt that heads will roll at these institutions because of these errors (sorry, a little Apocephalus humour there), the moral of this story is that the science content the majority of the public is exposed to is not exactly the best science content available! Hopefully, as scientists and science writers continue to use social media and blogs, the good stories I featured here will reach more of the people who would normally only see the “bad” versions, imparting a correct and positive experience with the fantastic research being done every day around the world!

Update (Jan. 07, 2012, 20:30) Brian Brown, a co-author on this study and the world’s expert on these flies, has expanded on the natural history and taxonomy of the flies involved in this research on his blog ‘flyobsession’. The remainder of the research team behind this study will be setting up a FAQ to help ‘clarify’ some of the errors I reported on above, and are also beginning a new citizen science project to begin understanding how far flung this parasitism is.

Core, A., Runckel, C., Ivers, J., Quock, C., Siapno, T., DeNault, S., Brown, B., DeRisi, J., Smith, C., & Hafernik, J. (2012). A New Threat to Honey Bees, the Parasitic Phorid Fly Apocephalus borealis PLoS ONE, 7 (1) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029639

BROWN, B. (1993). Taxonomy and preliminary phylogeny of the parasitic genus Apocephalus, subgenus Mesophora (Diptera: Phoridae) Systematic Entomology, 18 (3), 191-230 DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.1993.tb00662.x PDF Available HERE